Dialling up deception: ‘Vishing’ scams prey on human trust

Fraud, as a concept, is only slightly younger than the concept of a promise.

The advent of monetary and electronic advances in the past hundred or so years has only encouraged the practice and evolution of fraudulent tactics.

Phishing is no exception.

Representing 50% of all cyber-attacks, phishing continues to play out worldwide, combining known electronic fraud tactics and alternate forms of deployment.

'Vishing', also known as voice phishing, is an attack where fraudsters use the telephone to misrepresent their affiliation or authority in the hope that the victim will reveal credentials or other personal information.

Typically, fraudsters obtain the personal information of the victim and initiate an unsolicited call claiming to be from an organisation the victim trusts, such as a bank, government agency, or other service providers.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) recently warned of a sophisticated phone scam, manipulating Australians for a reported $830,000 in November.

The scam uses a method known as ID spoofing to make it appear as though the fraudsters are calling from a legitimate source.

While vishing accounts for less than one percent of total phishing-type attacks, it remains a very real threat as victims are more likely to be convinced by the personal touch of a human voice than an impersonal touch of an email.

Reverse Vishing

Vishing scams, traditionally believed to originate from an inbound call, are now being deployed in reverse.

Instead of the fraudster calling out to the victim, the victim calls out to the fraudster – this is known as 'reverse vishing'.

How does it work?

Perpetrators of this scam use the internet to push false information to the top of search results.

A common way to accomplish this sort of 'SEO poisoning' is to seed the false information throughout legitimate web pages, social media posts, online help forums and media comment sections, using keywords known to generate search traffic.

One recent example tracked by RSA involves the publishing of fake customer care numbers alongside legitimate physical locations on Google Maps.

Customers searching for business contact information are instead directed to a phone number operated by a fraudster.

This scheme has proven to be highly effective as it is very common for everyday Australians to search Google for the location or contact information of a business.

The absolute trust in search results can result in unsuspecting victims to call fraudsters, thus revealing sensitive personal information or credentials.

Social Channels

Social media is another channel that is frequently used in an attempt to reach unassuming victims.

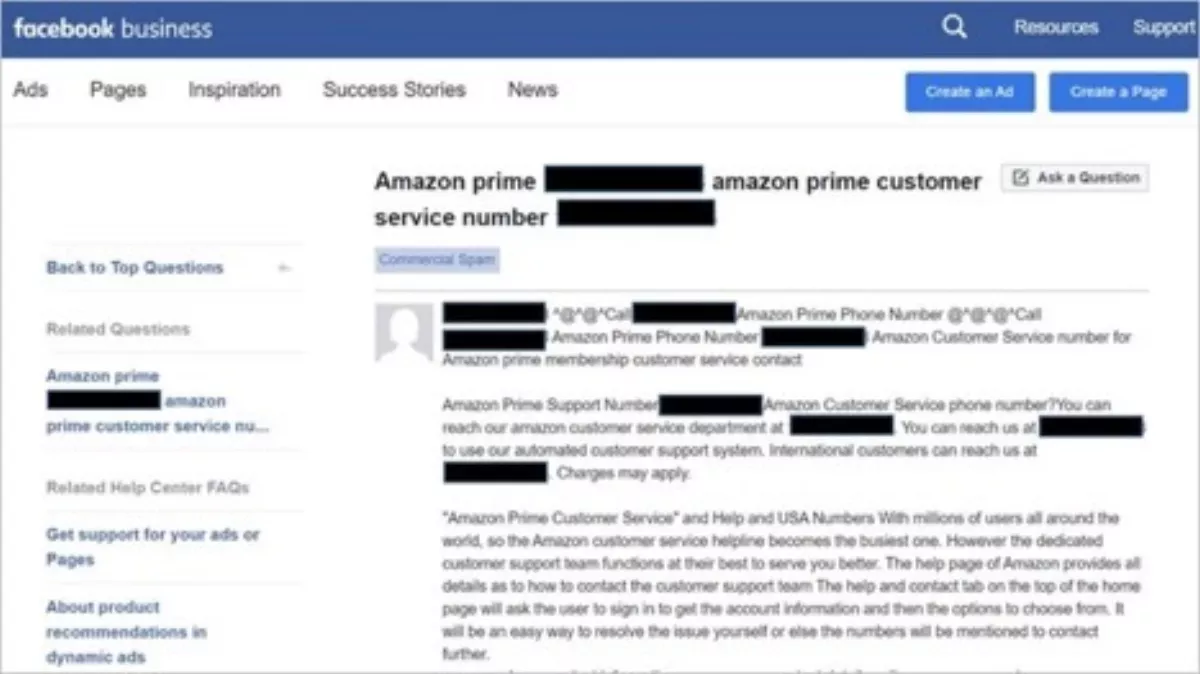

In the sample post below, a fraudster uses Facebook to try to direct consumers to a fake Amazon Prime customer service number.

Why are fraudsters reverse phishing?

While it's easier to create a false email address or social media account, phone numbers can be easily bought, sold and transferred, especially if obtained from the abundant illicit providers in the cybercriminal community.

Again, victims are more likely to reveal sensitive information through a personalised phone call, as opposed to an unsolicited email.

Second, using a phone number might be an effort to hamper any rapid attribution and takedown efforts. Oversight and takedown requirements, authority and processes for phone numbers are different from other electronic media in most countries.

How to encourage vigilance in an organisation

Neither SEO poisoning nor phone fraud are new tactics, but the combination and nuance of this particular type of attack is notable for its seemingly calculated tactics meant to prey on human trust.

Vigilance and knowledge are the best bet to prevent becoming a victim.

Given the tactics discussed, there are a few methods to encourage cybersecurity awareness in an organisation:

- Exercising caution when searching for important numbers on the web: The easiest and most secure way to find the correct contact information for a bank, telco, or any other service provider is by looking at official correspondence from that organisation. Statements, bills, invoices, and even credit and debit cards all include contact information for customer service.

- Never revealing sensitive information: The truth is that, like many companies have warned their customers, most organisations will never ask for sensitive information, including passwords and PIN codes, over the phone.

- Calling for help: If there is suspicion of a scam or fraudulent activity involving any financial information, the first step is to immediately contact the financial service provider. Following this step, it is also highly encouraged to report any potential scam to the appropriate authorities. For example, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) provides a Scam Watch – Report a scam.